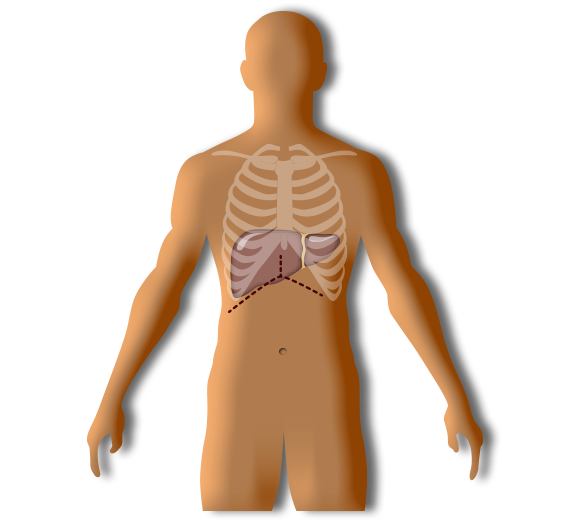

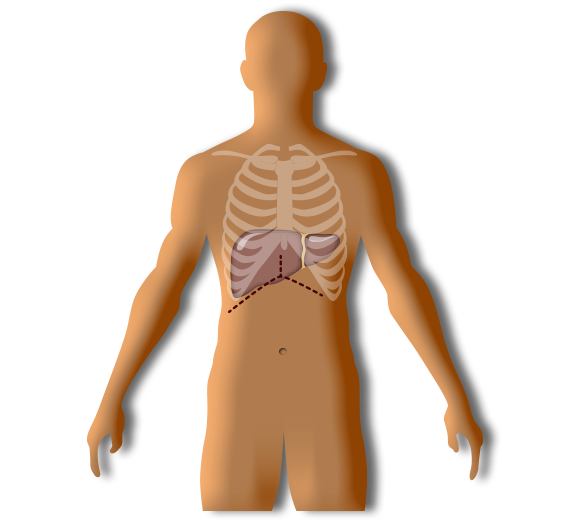

Incision

You’ll be lying on your back, with most of your body covered in sterile sheets. Your skin will be cleaned with a disinfectant solution, and the surgeon will then make a large incision along the lower arch of your ribcage. The cut will be about 15 – 18 inches in length, and may require a secondary cut upward, giving it the shape of an upside-down ‘Y’. Your skin will be pulled open to expose your abdominal cavity, and will be held in that position with several retractors.

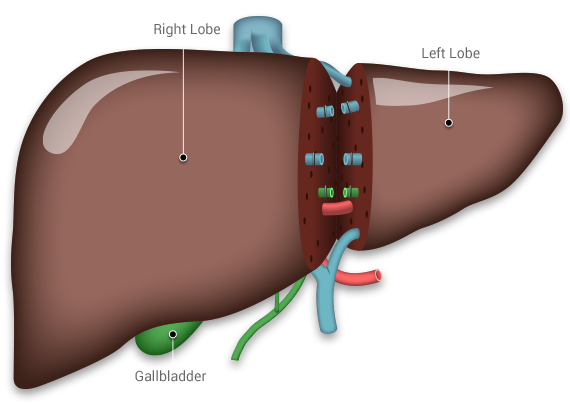

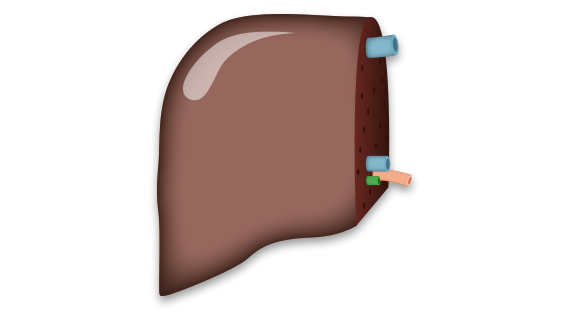

Lobe Separation

The surgeons will use a harmonic scalpel to separate the selected liver lobe. The harmonic scalpel tool cuts through tissue by vibrating very fast, burning your liver tissue at the same time. This burning action is important because it cauterizes most of the small vessels it touches, which minimizes bleeding. Larger vessels will be ligated (sewn shut instead of cauterized), because they will be needed to connect the liver to the recipient.

The liver has four lobes. If you’re donating to an adult your size, the surgeons will remove your right lobe, which makes up about 60% of your liver volume. If you’re donating to a child, you’ll donate part of your left lobe, which can range from 30-40% of your liver volume.

Lobe Transplant

Once the lobe has been separated from all vessels and connective tissue, the surgeons will take it out of your body. The assistants will flush the blood left inside, and place it in an iced preservative solution to minimize tissue decay. The supporting nurses will carerfully transport it to the operating room next door, where the recipient’s surgery will already be underway.

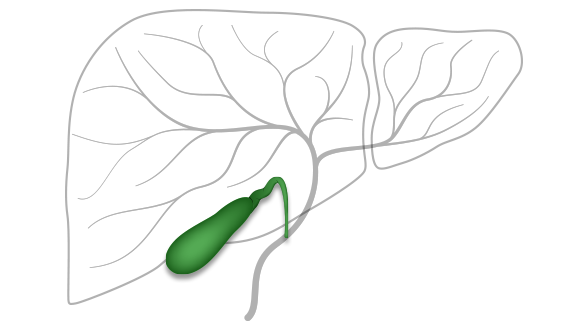

Gallbladder

The gallbladder stores bile that's produced by the liver until it's needed for digestion. Your gallbladder will be permanently removed during the donation surgery to avoid complications that may require a secondary operation. Some of these complications may include biliar leakage, or gallstones. Having no gallbladder has a very small impact on your digestive function, so the benefits outweigh the disadvantages.

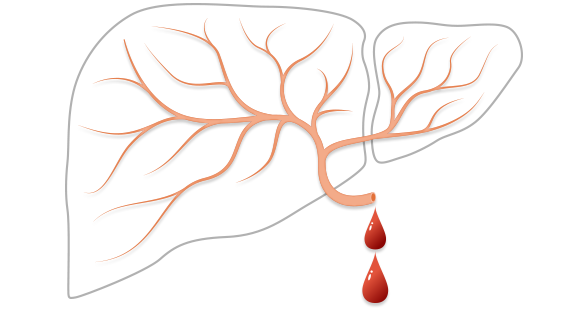

Potential Bleeding

Cutting through the liver is the riskiest part of the operation. The liver has many blood vessels running through it, so the surgical team must be very careful to stop all veins and arteries from leaking in a timely manner. With this in mind, we’ll have a backup unit of blood that you will have donated the previous week, in case you need a blood transfusion.

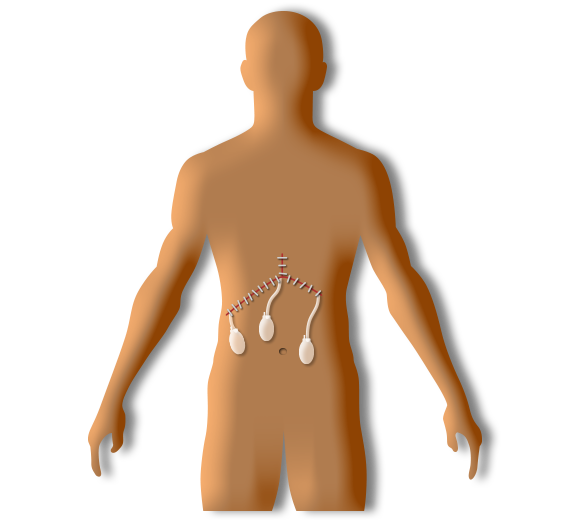

Finishing Steps

The surgical team will check that all blood vessels and bile ducts are safely contained. They will place drainage tubes (called Jackson-Pratt drains) along the surgery area to allow the escape of fluids that accumulate during recovery. Finally, your incision will be closed with staples. The team of anesthesiologists will take you off general anesthesia, and you’ll be taken to the PACU for close observation.